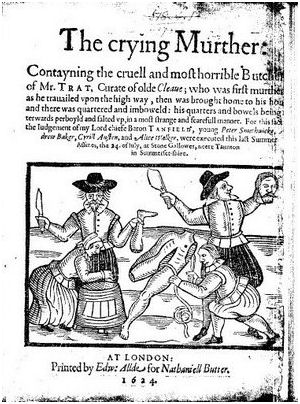

The awful plot against Curate Trat, of Old Cleeve Somerset, 1623

In the text of the day -

The crying murther Contayning the cruell and most horrible butchery of Mr.Trat, curate of old Cleave; who was first mu[rthered] as he trauailed upon the high way, then was brought home to his house and there was quartered and disemboweled: his quarters and bowels being afterwards perboyled and salted up, in a most strange and fearefull manner.

For this the judgement of my Lord chiefe Baron Tanfield, young Peter Smethwicke, An]drew Baker, Cyrill Austen, and Alice Walker, were executed this last summer Assizes, the 24. of July, at Stone Gallowes, neere Taunton in Summerset-shire (1624).

This really is an extraordinary case. In general, 16th and 17th century murderers come across as poor planners: impulsive, and liable to self-incrimination by word, deed, or failure to dispose of material evidence.

The man who in all likelihood plotted this murder came up with a very elaborate scheme, one which failed because it had too many people in on the secret (and two of them chronically loquacious).

The quarrel between Smethwicke and the curate Trat was started by a third man, one Brigandine, who was the parish’s incumbent, and who has let Trat hold the curacy for him in return for a fee. He finally decided to resign the incumbency completely to his curate. This offended Peter Smethwicke and his son: Brigandine was the senior Smethwicke’s step-father, and they considered him to have promised the gift of the parish to them.

Battle was joined, with real venom: Trat had been unfortunate enough to lose his wife in an accident: ‘His wife (being a feeble, sickly and weak woman) went to gather Limpets, (a kind of shell-fish which sticks upon the Rockes in that Sevearne or midland sea, deviding England from Wales’. She had fallen in and drowned while he fished from the beach some distance away. The Smethwickes accused him of her murder, but he was cleared of this charge, and they were disgraced locally for their accusation.

They had then tried another way to discredit the curate: he was lured out to supper, and while he was from home, someone broke into his house, stole his clerical gown, and went out and did some injury to a country woman: this in the dark, she was meant to accuse Trat, but he again escaped with his reputation intact. Meanwhile, Trat, reported in the pamphlet to have been not the greatest of clerks, but good at thundering out against the vices of his parish, made what response he could with a particular address to the sins of young Peter Smethwicke.

So the Smethwickes decided to murder him. Their plot was baroque in its complexity. First, he was ambushed and killed. His body was then taken back to his own house, and there it was dismembered. I suspect that Alice Walker had been induced to join the conspiracy for known skills at preparing ham. Poor Trat’s head and genitals were removed and burned. His arms and legs were disjointed, and placed, with his viscera, in large earthernware jars, salted. His cadaver was similarly placed in a large tub upstairs.

The plan here was to make the body unidentifiable, and conceal the date of the death.

With the curate vanished, local gossip tended to accuse his chief antagonist of having something to do with it. But the elder Smethwicke had another aspect to his plan, sending his ‘innocent’ and wrongly accused boy off to London, where Peter junior rather overdid the determination to establish an alibi for him (for a certain date), by very specifically asking an acquaintance to note that they were together in London on a particular day.

During this time, another accomplice set off on another impersonation of the missing (and now dead) curate. This accomplice, never named, ‘came to John Foards house of Taunton the Bowyer, a man who had seen Trat, but did scarce know him, or now remember him, and told him that he was M. Trat, the Curate of Old Cleeve.’ From there this accomplice-imposter journeyed to Ilminster, and told the same tale, and at Blanford in Dorset, told the most audacious part of this story. Somehow Smethwicke knew that the incumbent there, Parson Sacheverell, had been at Oxford years before with Trat. The accomplice identified himself as Trat, but refused to get off his horse, saying ‘I have stabd a man in my house where I live, of whose life I am doubtful’. Sacheverell was of course shocked, and urged him to return to Old Cleeve. The impersonator of Trat told the story of having met a man in Dunster who had recently come from Ireland, and this man had begged money from him. This fictitious person had then been given lodgings in Trat’s house, but at breakfast, had crossed himself superstitiously before eating. ‘Trat’ had admonished him for this, they had quarreled, the quarrel had descended to blows, ‘Trat’ had struck the Irishman with a knife, and was now fleeing the scene.

So, what Smethwicke was aiming for was an unidentifiable corpse in Trat’s house, which would be taken to be the victim of a killing carried out by Trat! So detailed was the plan that a suit of green clothes had been left, bloodied, in Trat’s house (no owner was ever found for this suit, which was merely placed there to substantiate this figmentary Irishman). The plot would have to have maintained that Trat had done far more than he had so strangely confessed to down in Blanford, but had both killed and butchered his victim, and made his head disappear completely, before running aimlessly away blabbing to old college acquaintance en route. Smethwicke junior would be in the clear, for the confessions of the imposter would narrow down the date of the murder to a time when he was up in London.

It must have taken a deal of resolution to carry out the processing of the body, and this is where things began to go wrong. Alice Walker was clearly aware that they had made rather hasty work of the preserving job on the body parts. During the fortnight in which the curate had vanished, she had unwisely quipped that ‘if the Parson did not come home the sooner, his powdered Beef would stinke before his coming’.

So it proved. Neighbours could smell putrefaction emanating from the house, the parish officers broke in, and discovered the source of the stench.

Meanwhile, another of the murder party had left the scene to work twelve miles away. When news of the murder reached that parish, he could not resist giving a far better account of the circumstances of the murder than the informant had just given, apparently only pausing in his tale to wipe his face with a bloody napkin. He fled this scene, but was finally apprehended in Wiltshire, where he unwisely bragged of having friends who would pay to help him out of prison, or they would ‘smoke for it’.

Meanwhile the justices were unraveling the story back in Somerset. A particular known mark on one of the fingers had more or less been identified as showing the victim to have been Trat. Justice Cuffe had raked about in the ashes in the hearth at Smethwicke’s house, and found residual bits of skull, neck vertebrae, and teeth. Out in the garden, positioned behind some strong smelling herbs, a pot of stinking blood was found. Andrew Baker, one of the murder party, was ordered to lift the pot out very carefully, but spilt it, with a deliberate intent obvious to those who witnessed it.

The panicky Andrew Baker had anyway been traumatized by what they had so meticulously done to Trat, as he was by this stage reportedly given to crying out in his sleep ‘let us fly Mr Peter, let us away or else we shall be all undone and hanged’.

Smethwicke senior clearly had many strong local connections, and to save his son, arranged a packed jury to sit on the case that was brought. But now Lord Tanfield stepped in, and initially postponed the trial, but with new evidence coming forward, pushed ahead with it, having completely changed the composition of the jury.

The pamphlet ends with all four of the murder party dead, hanged in Taunton, but without any confession. Alice Walker almost confessed, but then failed to do so, though the usual ministers pumped her to clear her conscience. The elder Smethwicke, who had gambled so much for the money remains in prison. Some consider him guilty; others consider none of the accused to have been guilty. The pamphleteer feebly ends with an admonishment that we should all learn to hold our tempers in check.